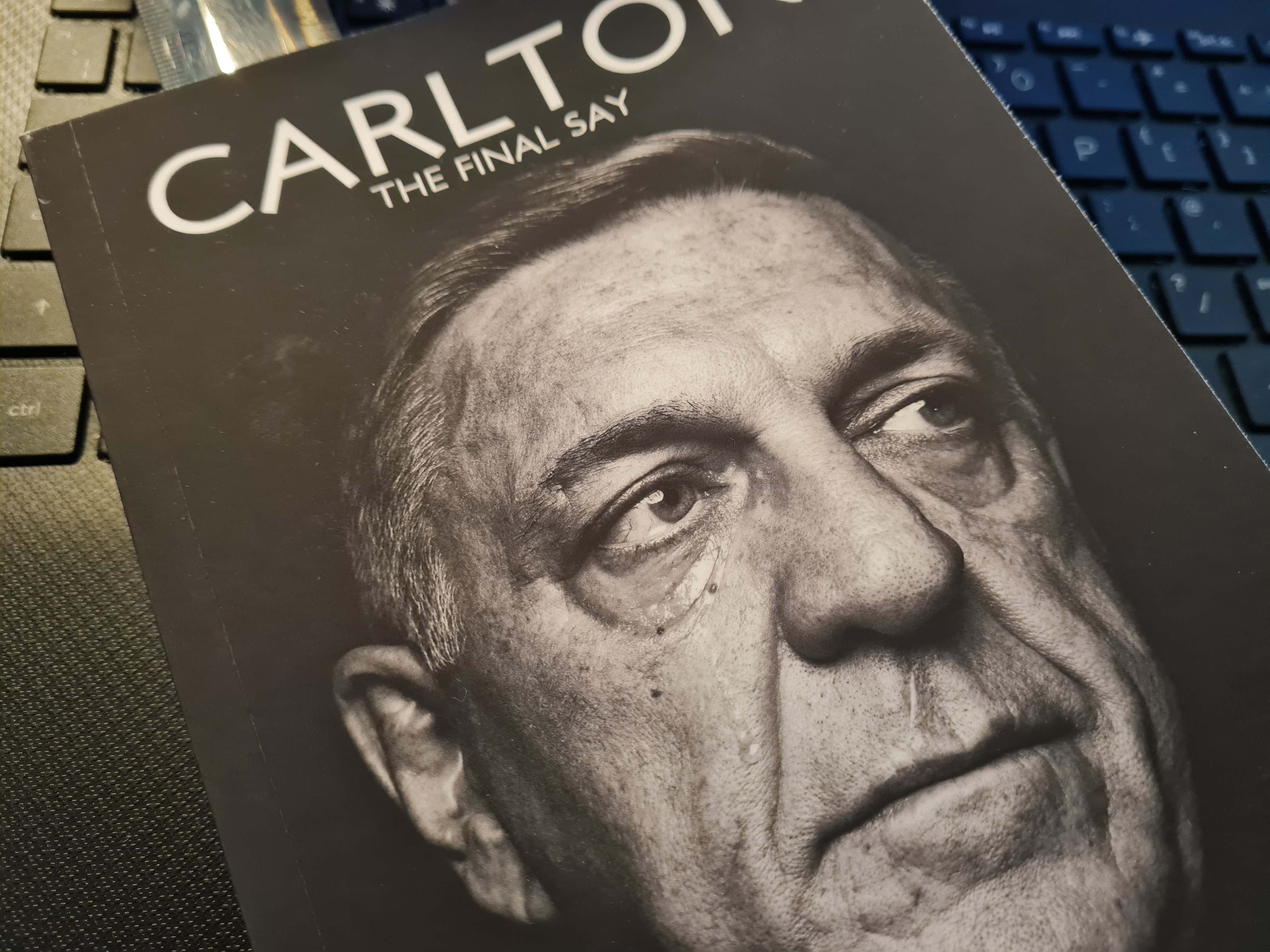

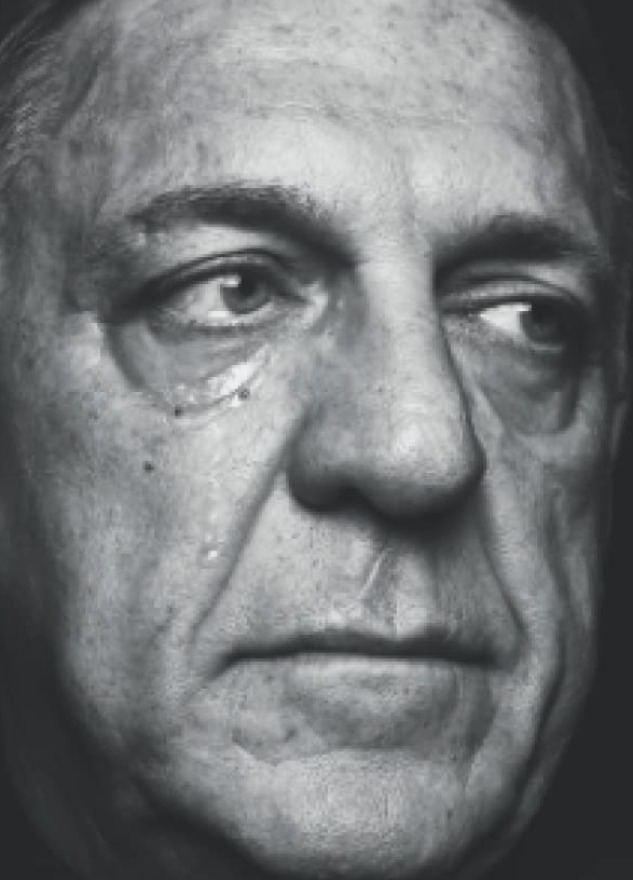

After reading Carlton’s book “The Final Say” I wasn’t left feeling he’d threatened national security, territorial integrity, or public safety. Instead he spoke of his life and perspectives on matters that affected it. With regards to health matters, he spoke of his own family for all of this is his right. It’s also the right of a man to convey a story—his version of events—the way they unfolded for him and for this to happen with the help of a co-author.

This right, the right to tell your story through your co-author—and in this case it’s Jason Allday—is ruffling some feathers. Let’s face facts, books like this often do. Freedom of speech coming at a price when someone doesn’t want you to have a voice. Protection of health or morals, and the protection of the reputation of others are the final aspects of the Human Rights Act 1998 that allow us freedom of speech—the same act that allows others their say on the same subject in question.

Whatever your views on how anyone has lived out their past, this is my view… books such as Carlton’s are a valuable source of social history without which a large chunk of society is lost if events are not recorded. Within the pages we learn of social change, injustice, triumph, grief, and all manner of concepts that wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for the foresight it takes in putting pen to page. That takes courage.

An event that took place in 1995 is of course at the epicentre of yet more controversy, something that surely needs placing to rest or investing by an independent police force team if the first haven’t done the investigation justice. Not an investigation that’s needed to be carried by an author I’ll not name here—nor should he be silencing anyone who voices differing perceptions to his own. Perceptions that differ to the official investigations and to his original views I might add.

I’m of course talking about the Rettendon murders—also branded the Range Rover killings and the Essex Boy murders or however else it may have been phrased over the years. Carlton, my apologies for dragging this up but some of my readers will not know the history of this case:

Three friends, Tony Tucker, Patrick Tate and Craig Rolfe were shot, execution style in a gateway along Workhouse Lane in Rettendon in Essex on 6th December 1995. This had followed the death of a young girl from Latchingdon (also in Essex and not far from this scene) after taking ecstasy. Leah Betts fell into a coma, her ex-police officer father shared photographs of her across the news and other media which touched the hearts of the nation. At the first inquest for Leah’s death it was found that due to the amount of water she had consumed she’d slipped into a coma. Subsequently, at a further inquest it was concluded that Leah would have survived either the water consumption or the ecstasy alone but not the combination. She died on 17th November, less than a month before the three friends were found dead in the Range Rover.

Rumours soured through the press and it wasn’t long before these two events were linked. It was at this time (and not before) that the “Essex Boys” gained their notorious name for this wasn’t how they were known when they were alive.

What we must ask is why should silence be an option? What could possibly have been said in “The Final Say” that’s so upsetting to one person to elicit legal action against Jason Allday—not the person who was friends with one of the murdered men, but the man to whom Carlton entrusted his story and who put that pen to the page. That makes no sense to me.

Desperate times indeed. Why the need to silence this book? That gets me asking some serious questions.

You are able to help him at the link below

Go Fund Me