In memory of

Private Harold Stanley Glynn

(1895-1917)

Glory to thee, as you march to Arras

Towards foreseen doom, into the unknown.

A battle too far, man to the slaughter

Bodies falling, sprits rising. Cannons blown.

Glory to thee, as you try to advance

Clouds made of smoke, the thunder of guns.

The rain that falls, not of water but blood

The women back home, losing husbands and sons.

Glory to thee, as you lay down to die

Your bodies giving up, so we might live.

Battlefields bathed in your blood

The ultimate sacrifice you could give.

Glory to thee, your spirt lives on

To the ghosts of Arras, and all of WWI

For the sacrifice you gave in that fateful battle

The lives you gave, can never be undone.

Glory to thee, as we all look back

Remembering your brave acts

For all the ghosts of Arras

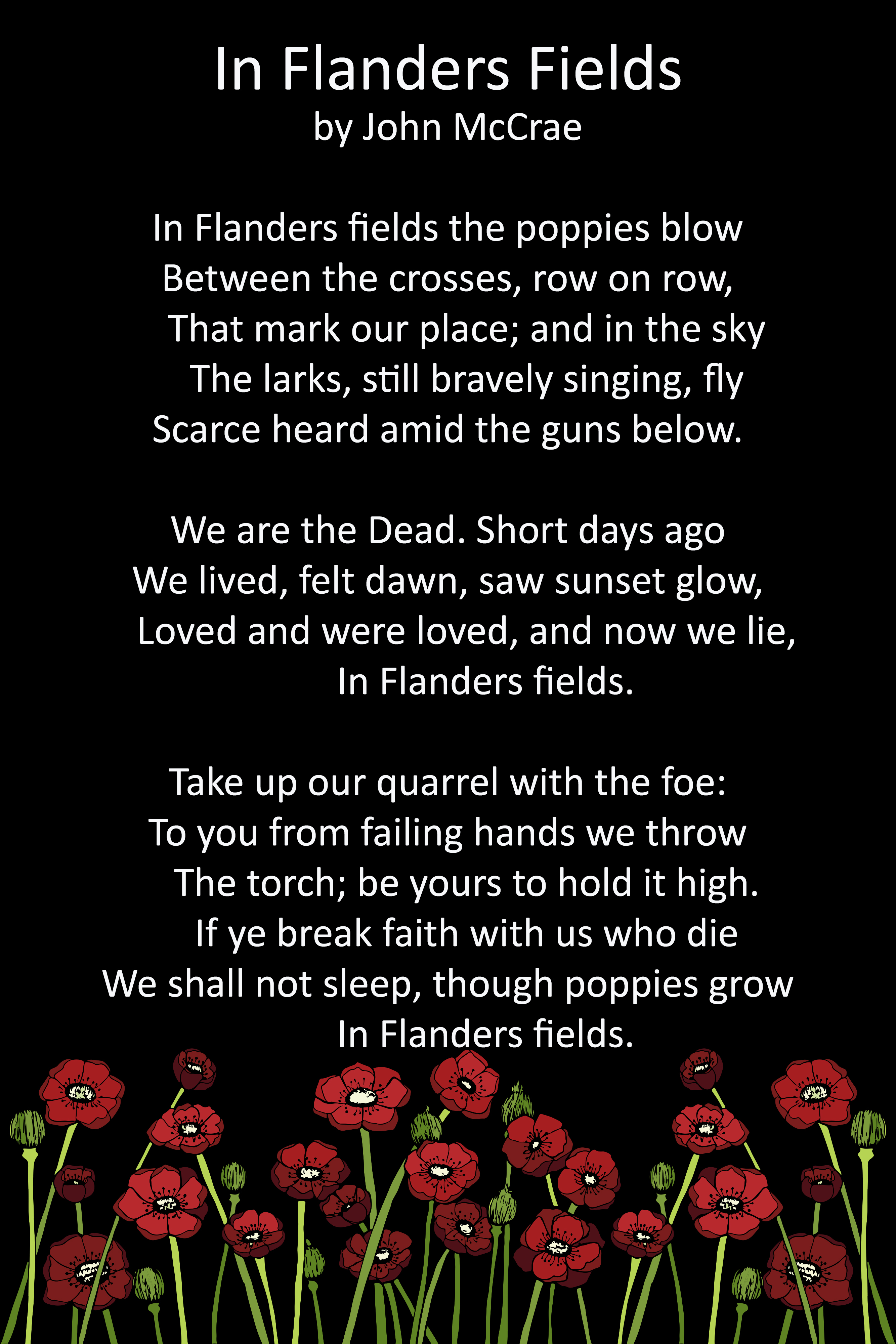

And all the fallen, a poppy we bring.

(© Donna Siggers)